PFAS Overview

Per-and Polyfluroalkyl Substances (“PFAS”) are a synthetic class of more than 4,700 man-made chemical compounds that have been used in a variety of consumer products to resist or repel stains, grease, soil and water. Since the 1940s Perfluorooctanoic acid (“PFOA”) and PFAS have been used in consumer and industrial products, including clothing, carpets, rugs, upholstered furniture, food packaging including fast food wrappers, cardboard, paper, firefighting foam, chrome plating and other products like non-stick cookware. PFAS have more recently come under increasing scrutiny because they persist in the environment and are known as “forever chemicals”. PFAS are believed to be in almost 99% of the US population and are alleged to be linked to certain health problems.

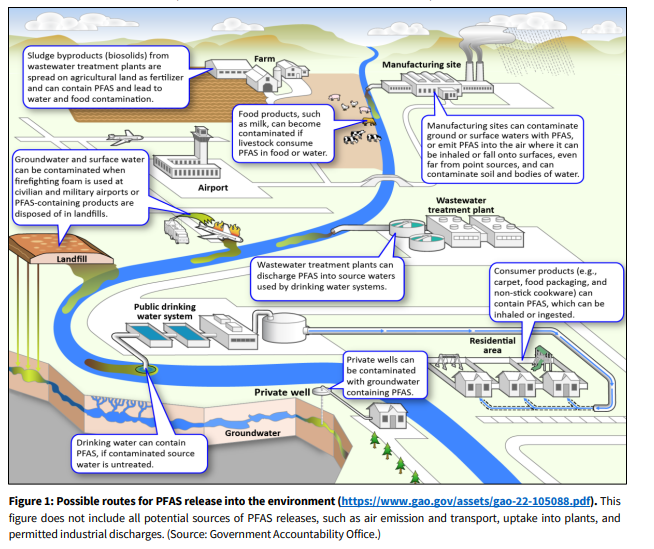

Image source: PFAS Technologies GAO-22-105088 (page 4)

PFOA can enter groundwater from multiple sources, including sewage treatment plants, industrial sites, landfills, and places where it is used in firefighting foam such as airports, firefighter training sites, and military installations. Fish and shellfish can take up PFOA from water contaminated with the chemical. PFOA can be released into the air and into food from some older non-stick cookware and some new imported non-stick cookware. PFAS are also contained in imported products and products containing post-consumer recycled materials.

The Evolution of the United States Environmental Protection Agency’s (“EPA”) PFAS Strategy

In 2006, the EPA initiated the global PFOA Stewardship Program: eight major manufacturing companies of PFOA and other longer-chain perfluorinated carboxylates committed to achieving a 95 percent reduction in both facility emissions and product content levels by 2010, and elimination by 2015. All companies met the established goals.

The EPA issued the third Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule (“UCMR 3”) in May 2012. The UCMR 3 required monitoring between 2013 and 2015, for 30 substances of all large public water systems (“PWS”) serving more than 10,000 people, and 800 representative PWS serving 10,000 or fewer people. Six PFAS compounds were included in the UCMR 3 contaminant list. Of these six PFAS compounds, only two, PFOA and Perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (“PFOS”), had EPA provisional health advisory levels, and one, perfluorobutane sulfonic acid (“PFBS”), had published toxicity values.

The current understanding of PFOS and PFOA toxicities in humans is limited. PFOS and PFOA are toxic to laboratory animals and there is suggestive evidence that PFOS and PFOA may cause cancer. In an effort to raise awareness and provide a margin of protection from a lifetime of exposure to PFOS and PFOA, the EPA published a lifetime health advisory level (“LHA”) of 70 parts per trillion (“ppt”) for drinking water in 2016. The EPA’s LHA is non-enforceable and non-regulatory, however, institutions such as the Department of Defense, among others, have taken actions to restrict or shut down water systems that contain concentrations of PFOS and/or PFOA above the EPA’s LHA level. The California Division of Drinking Water has also established Notification Levels for drinking water of 6.5 ng/L for PFOS and 5.1 ng/L for PFOA. The California Response Level for drinking water is 40 ng/L for PFOS and 10 ng/L for PFOA.

The EPA issued its PFAS Strategic Roadmap: EPA’s Commitments to Action 2021-2024 stating goals, objectives and key actions for setting standards and regulations for PFAS. The recently proposed National Primary Drinking Water Regulation is part of the EPA’s plan.

On June 15, 2022, the EPA Office of Water issued a drinking water LHA for PFOA, PFOS, GenX chemicals, and PFBS. The LHA is 0.004 ppt for PFOA, 0.02 ppt for PFOS, 10 ppt for GenX chemicals, and 2,000 ppt for PFBS. Again, the EPA’s LHA is non-enforceable and non-regulatory.

Recently, the National Science and Technology Council announced that the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) released a state of science report on PFAS. The report focuses on the current science of PFAS as a chemical class, identifies scientific consensus, and portrays uncertainties in the scientific information where consensus is still sought. This report explains some of the potential problems of PFAS while also pointing out research data gaps that will be used for research and development of the Federal Government’s PFA strategy.

PROP 65 and PFAS

California’s Safe Drinking Water and Toxic Enforcement Act of 1986 (“Proposition 65” or “Prop 65”) was designed to provide consumers with information regarding potential exposure to chemicals identified as carcinogens and/or reproductive toxicants. Proposition 65 requires “clear and reasonable” warnings to be placed on products where exposure to a chemical on the Proposition 65 list would exceed a safe harbor level as a result of normal, foreseeable use of the product. Prop 65 applies to companies located in California or to businesses supplying, manufacturing, distributing or selling products to anyone in the state of California.

California has added PFAS to the list of chemicals requiring consumer warnings under Proposition 65. Three other PFAS (PFDA, PFHxS, and PFUnDA) are currently under review by Office of Environmental Hazard Assessment (“OEHHA”) for possible reproductive toxicity.

On October 26, 2022, the National Law Review reported a nearly 100% increase in the number of PFAS enforcement notices. Prop 65 Notices of Violations (“NOVs”) have targeted products such as outerwear clothing and rain jackets, baby bibs, bath pillows, duffel bags, umbrellas, shower liners, crib mattress pads, tablecloths, paper straws and cosmetics. Prop 65 penalties can be as high as $2,500 per violation per day and may include attorneys’ fees and costs.

The prospect of Proposition 65 enforcement and litigation for products containing PFAS is uniquely challenging for regulated businesses because of the prevalence of PFAS in many products and environments, and because PFAS can be detected at extremely low levels. Plaintiffs who detect these low levels of PFAS in products, work areas, or the environment can file NOVs against businesses if they fail to warn under Proposition 65. Further, the OEHHA has not established specific safe harbor levels for any of the listed PFAS. This creates challenges for companies who may perform exposure assessments to determine if certain PFAS exposures require a warning.

Prop 65 generally applies to manufacturers, suppliers, importers and retailers of products. PFAS continue to be the focus of state chemical legislation. California and eight other states have passed broad prohibitions on PFAS in food packaging in the future. California banned the manufacture and sale of cosmetics (AB 2771)[1], clothing and textile (AB1817)[2] items containing PFAs beginning January 1, 2025. Maine has also banned certain products containing PFAS.

Once the proposed EPA regulations take effect, the list of Prop 65 PFAS will likely increase and possibly act as a floor for safe harbor limits. It is probable that private enforcement Prop 65 lawsuits will increase in number and possibly seek warnings for any PFOA or PFOS that is detected above zero.

Importers, downstream product assemblers/manufacturers and retailers may not be aware of the presence of PFAS in products they sell or offer to sell to California consumers. These companies should start adding PFAS to their planning. For example, companies should consider obtaining assurances or disclosures from suppliers of products and materials about the presence of PFAS in their products.

Because of the small size and mixing of chemicals, testing for PFAS can be difficult and expensive. Companies should include testing as part of a comprehensive compliance program and we recommend coordinating such efforts and discussions with legal counsel.

Furthermore, companies that prophylactically provide Prop 65 warnings whether or not chemicals are at levels requiring Prop 65 warnings to avoid potential Prop 65 liability should consider whether the warning creates a risk given state and federal regulations and restrictions on PFAS.

Regulating PFAS and Other Areas to Watch

CERCLA and PFAS

On March 14th and 23rd, 2023, the EPA held its second listening session on a Potential Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (“CERCLA”) Enforcement Discretion Policy for Addressing PFAS Contamination at Superfund Sites. (CERCLA PFAS Enforcement Listening Sessions | US EPA) In August of 2022, the EPA proposed to designate PFOA and PFOS as hazardous substances under CERCLA. The EPA may finalize these designations in August of this year. If this occurs both the number of Potentially Responsible Parties (“PRPs”) and the costs associated with investigation and cleanup could dramatically increase.

The EPA indicated that it intends to concentrate its efforts on manufacturers, facilities and other industrial parties whose actions result in significant releases of PFAS. The EPA also indicated that it does not intend to pursue CERCLA enforcement for PFAS contamination against water utilities and publically owned treatment works (“POTWs”), publically owned and or operated municipal solid waste landfills, farms applying biosolids and certain airports and fire departments.

NPDES and PFAS

The National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (“NPDES”) regulates point sources that discharge to waters of the United States. On April 28, 2022, the EPA issued a memorandum that in part addressed the EPA’s attempt to limit PFAS discharges to waterways. The memorandum recommended the monitoring by draft analytical method 1633 of 40 detectable PFAS parameters at least quarterly for industrial dischargers and POTWs. In addition this memorandum included Best Management Practices (BMPs) that included

“i. Product elimination or substitution when a reasonable alternative to using PFAS is available in the industrial process.

ii. Accidental discharge minimization by optimizing operations and good housekeeping practices.

iii. Equipment decontamination or replacement (such as in metal finishing facilities) where PFAS products have historically been used to prevent discharge of legacy PFAS following the implementation of product substitution.”

Impact of PFAS Regulations

Water users of all types – domestic household, municipal or industrial, agricultural – are all impacted by contaminated water supplies. Water quality standards vary for the intended use of the water, whether it be for drinking water or irrigating crops. Even though the PFAS contamination issues typically originate with groundwater supplies, diminished reliance on groundwater could increase the need for surface water supplies, which places further strain on the water rights and water supply systems. As such, water quality and water rights are inextricably intertwined with surface water and groundwater.

The EPA is using its resources under various programs to effectuate its PFAS Strategic Roadmap. The projected costs to water suppliers and industry are expected to be significant. In December 2021 the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act included $10 billion to address PFAS in drinking water. On February 13, 2023, the administration announced the availability of $2 Billion in Bipartisan Infrastructure Law Funding to States and Territories to Address Emerging Contaminants like PFAS in Drinking Water.

The OSTP state of science report on PFAS explains the current level of understanding and gaps of information. CERCLA designations might occur in August and NPDES changes will also occur. Recently the EPA recently issued its proposed National Primary Drinking Water and indicated its intent to set a PFAS standard before the end of the year.

As a result, a significant increase in Prop 65 NOVs and lawsuits for entities conducting business in California is expected. Water suppliers, industry including manufacturers, suppliers, importers and retailers of products should consider whether PFAS affect their business to assess their legal and regulatory risk and if necessary begin to plan their PFAS strategy for potential risk mitigation and compliance.

If you have any questions concerning PFAS regulations, please contact your AALRR attorney or the authors of this Alert. For an overview of the EPA’s proposed regulation regarding PFAS in national drinking water, please see our Alert.

[1] This regulation applies to cosmetics containing: 1) “PFAS chemicals that a manufacturer has intentionally added to a product and that have a functional or technical effect on the product.” 2) “PFAS chemicals that are intentional breakdown products of an added chemical.”

[2] PFAS are regulated when “intentionally added to a product that have a functional or technical effect in the product” or contain more than 100 ppm total organic fluorine in January 1, 2025 or more than 50 ppm by January 1, 2027. Extensions for this deadline apply to manufacturers of outerwear designed for extreme rain conditions or extended immersion in water or wet weather, until January 1, 2028, but must be labeled as containing PFAS beginning 2025. Exemptions apply to personal protective equipment such as firefighter gear.

This AALRR publication is intended for informational purposes only and should not be relied upon in reaching a conclusion in a particular area of law. Applicability of the legal principles discussed may differ substantially in individual situations. Receipt of this or any other AALRR publication does not create an attorney-client relationship. The Firm is not responsible for inadvertent errors that may occur in the publishing process.

© 2023 Atkinson, Andelson, Loya, Ruud & Romo

Attorneys

Partner562-653-3200

Partner562-653-3200 Partner949-453-4260

Partner949-453-4260